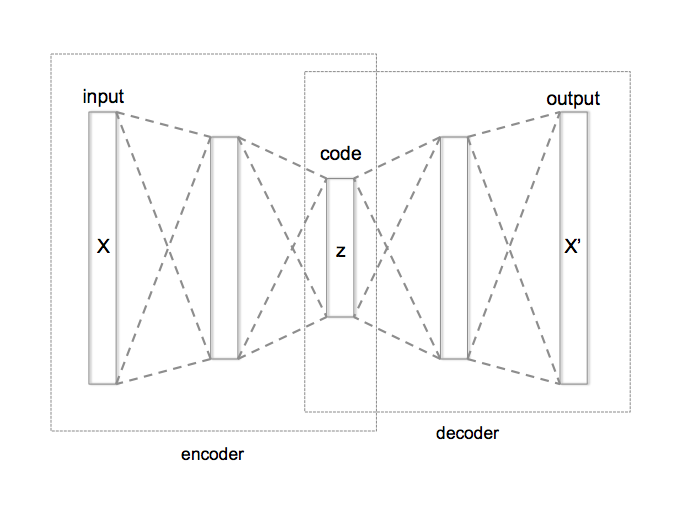

I love the simplicity of autoencoders as a very intuitive unsupervised learning method. They are in the simplest case, a three layer neural network. In the first layer the data comes in, the second layer typically has smaller number of nodes than the input and the third layer is similar to the input layer. These layers are usually fully connected with each other. Such networks are called auto-encoders since they first “encode” the input to a hidden code and then “decode” it back from the hidden representation. They can be trained by simply measuring the reconstruction error and back-propagating it to the network’s parameters. If you add noise to the input before sending it through the network, they can learn better and in that case, they are called denoising autoencoders. They are useful because they help with understanding the data by trying to extract regularities in them and can compress them into a lower dimensional code.

A typical autoencoder can usually encode and decode data very well with low reconstruction error, but a random latent code seems to have little to do with the training data. In other words the latent code does not learn the probability distribution of the data and therefore, if we are interested in generating more data like our dataset a typical autoencoder doesn’t seem to work as well. There is however another version of autoencoders, called “variational autoencoder - VAE” that are able to solve this problem since they explicitly define a probability distribution on the latent code. The neural network architecture is very similar to a regular autoencoder but the difference is that the hidden code comes from a probability distribution that is learned during the training. Since it is not very easy to navigate through the math and equations of VAEs, I want to dedicate this post to explaining the intuition behind them. With the intuition in hand, you can understand the math and code if you want to.

I start with a short history. Over the past two decades, researchers have been trying to develop a framework for probabilistic modeling that explicitly conveys the assumption being made about the data. The result of this effort has been probabilistic graphical models that combines ideas from graph theory and probability theory. Graphical models use a graph representation to encode a probability distribution over a set of random variables. Graph representation is a very flexible language that admit composability for building arbitrary complex models and provides a set of tools to perform reasoning (inference) about different nodes in the graph.

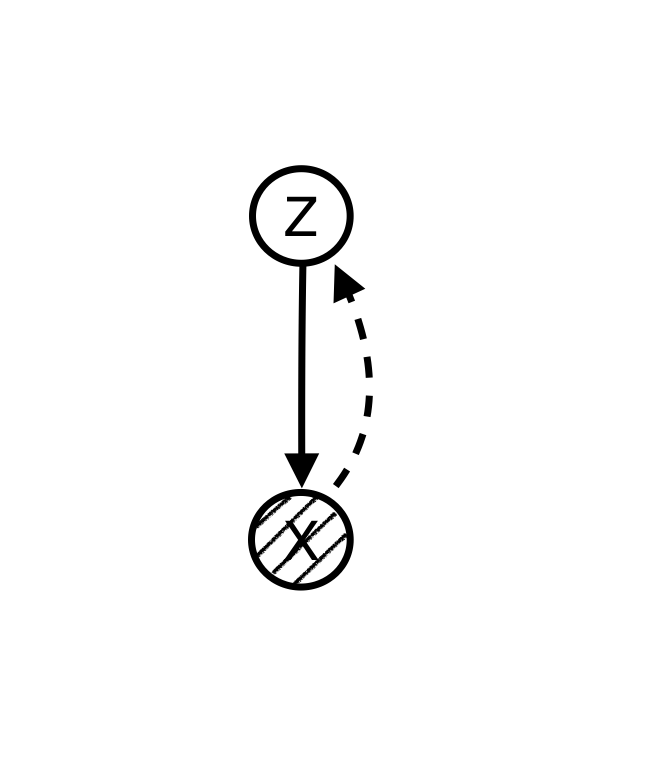

Using graphical models language we can explicitly articulate the hidden structure that we believe is generating the data. For example, if we believe that there is a hidden variable for each observable data point that is causing the data, we can make a model like this:

Since data points, , are observed while the nodes are unknown, we want to “infer” the hidden variables from known data points. The solid line shows the data generation path and the dashed line shows the inference path.

Reasoning (inference) about hidden variables in probabilistic graphical models has traditionally been very hard and only limited to very restricted graph structures. This issue had significantly limited our ability to build interesting models and perform reasoning on them in the past. However, in the past few years there have been some very exciting developments that have enabled us to perform approximate reasoning with scalable algorithms like stochastic gradient descent. This has triggered another wave of interest in graphical models.

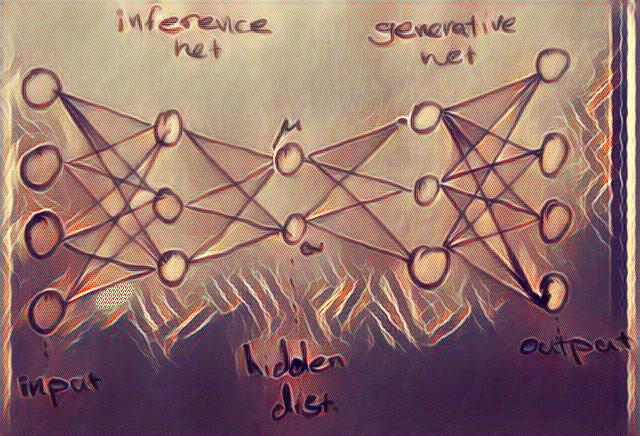

Recent developments come from the idea that directed graphical models can represent complex distributions over data while deep neural nets can represent arbitrarily complex functions. We use deep neural networks to parameterize and represent conditional distributions. Variational autoencoders are the result of the marriage of these two set of models combined with stochastic variational and amortized inference.

A variational autoencoder is essentially a graphical model similar to the figure above in the simplest case. We assume a local latent variable, for each data point . The inference and data generation in a VAE benefit from the power of deep neural networks and scalable optimization algorithms like SGD.

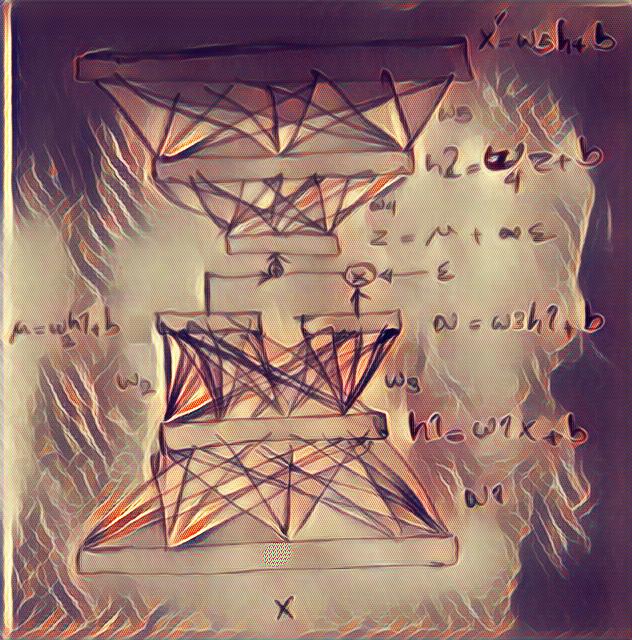

As can be seen from the picture above, in a VAE, the encoder becomes a variational inference network that maps the data to the a distribution for the hidden variables, and the decoder becomes a generative network that maps the latent variables back to the data. Since the latent variable is actually a probability distribution, we need to sample the hidden code from its distribution to be able to generate data.

In order to be able to use stochastic gradient descent with this autoencoder network, we need to be able to calculate gradients w.r.t. all the nodes in the network. However, latent variables, , in a graphical model are random variables (distributions) which are not differentiable. Therefore, to make it differentiable, we treat the mean and variances of the distributions as simple deterministic parameters and multiply the variance by a sample from a normal noise generator to add randomness. By parameterizing the hidden distribution this way, we can back-propagate the gradient to the parameters of the encoder and train the whole network with stochastic gradient descent. This procedure will allow us to learn mean and variance values for the hidden code and it’s called the “re-parameterization trick”. It is important to appreciate the importance of the fact that the whole network is now differentiable. This means that optimization techniques can now be used to solve the inference problem efficiently.

In classic version of neural networks we could simply measure the error of network outputs with desired target value using a simple mean square error. But now that we are dealing with distributions, MSE is no longer a good error metric. So instead, loosely speaking, we use another metric for measuring the difference between two distributions i.e. KL-Divergence. It turns out that this distance between our variational approximate and the real posterior distribution is not very easy to minimize either [2]. However, using some simple math, we can show that this distance is always positive and that it comprises of two main parts (probability of data minus a function called ELBO). So instead of minimizing the whole thing, we can maximize the smaller term (ELBO) [4]. This term comes from marginalizing the log-probability of data and is always smaller than the log probability of the data. That’s why we call it a lower bound on the evidence (data given model). From the perspective of autoencoders, the ELBO function can be seen as the sum of the reconstruction cost of the input plus the regularization terms.

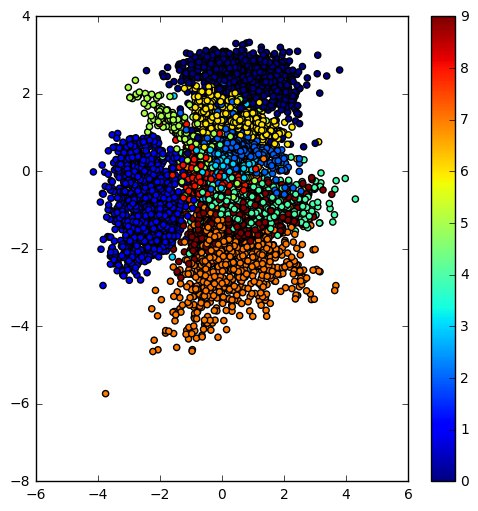

If after maximizing the ELBO, the lower bound of data is close to the data distribution, then the distance is close to zero and voila!; We have minimized the error distance indirectly. The algorithm we use to maximize the lower bound is the exact opposite of gradient descent. Instead of going in the reverse direction of the gradient to get to the minimum, we go toward the positive direction to get to the maximum, so it’s now called gradient ascent! This whole algorithm is called “autoencoding variational Bayes” [1]! After we are done with the learning we can visualize the latent space of our VAE and generate samples from it. Pretty cool, eh!?

Here is a high level pseudo-code for the architecture of a VAE to put things into perspective:

network= {

# encoder

encoder_x = Input_layer(size=input_size, input=data)

encoder_h = Dense_layer(size=hidden_size, input= encoder_x)

# the re-parameterized distributions that are inferred from data

z_mean = Dense(size=number_of_distributions, input=encoder_h)

z_variance = Dense(size=number_of_distributions, input=encoder_h)

epsilon= random(size=number_of_distributions)

# decoder network needs a sample from the code distribution

z_sample= z_mean + exp(z_variance / 2) * epsilon

#decoder

decoder_h = Dense_layer(size=hidden_size, input=z_sample)

decoder_output = Dense_layer(size=input_size, input=decoder_h)

}

cost={

reconstruction_loss = input_size * crossentropy(data, decoder_output)

kl_loss = - 0.5 * sum(1 + z_variance - square(z_mean) - exp(z_variance))

cost_total= reconstruction_loss + kl_loss

}

stochastic_gradient_descent(data, network, cost_total)

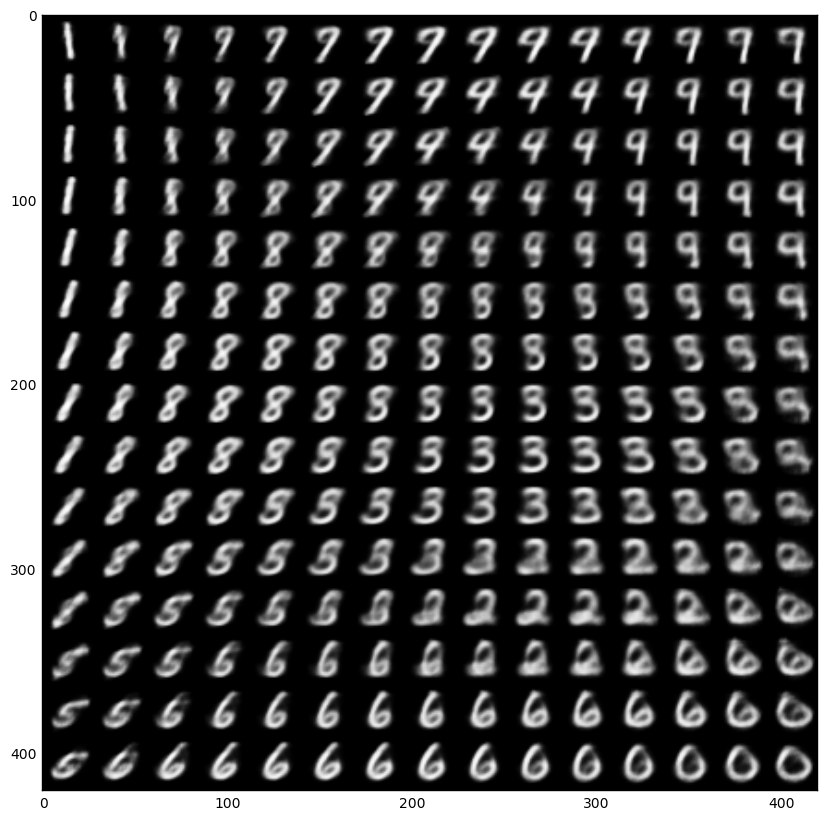

Now that the intuition is clear, here is a Jupyter notebook for playing with VAEs, if you like to learn more. The notebook is based on this Keras example. The resulting learned latent space of the encoder and the manifold of a simple VAE trained on the MNIST dataset are below.

|

|

Side note 1:

The ELBO is determined from introducing a variational distribution q, on lower bound on the marginal log likelihood, i.e. . We use the log likelihood to be able to use the concavity of the function and employ Jensen’s equation to move the inside the integral i.e. and then use the definition of expectation on (the nominator goes into the definition of the expectation on to write that as the ELBO) . The difference between the ELBO and the marginal which converts the inequality to an equality is the distance between the real posterior and the approximate posterior i.e. . Alternatively, the distance between the ELBO and the KL term is the log-normalizer . Replace the with Bayesian formula to see how.

Now that we have a defined a loss function, we need the gradient of the loss function, to be able to use it for optimization with SGD. The gradient isn’t easy to derive analytically but we can estimate it by using MCMC to directly sample from and estimate the gradient. This approach generally exhibits large variance since MCMC might sample from rare values.

This is where the re-parameterization trick we discussed above comes in. We assume that the random variable is a deterministic function of and a known ( are iid samples) that injects randomness . This re-parameterization converts the undifferentiable random variable , to a differentiable function of and a decoupled source of randomness. Therefore, using this re-parameterization, we can estimate the gradient of the ELBO as . This estimate to the gradient has empirically shown to have much less variance and is called “Stochastic Gradient Variational Bayes (SGVB)”. The SGVB is also called a black-box inference method (similar to MCMC estimate of the gradient) which simply means it doesn’t care what functions we use in the generative and inference network. It only needs to be able the calculate the gradient at samples of . We can use SGVB with a separate set of parameters for each observation however that’s costly and inefficient. We usually choose to “amortize” the cost of inference with deep networks (to learn a single complex function for all observations instead). All the terms of the ELBO are differentiable now if we choose deep networks as our likelihood and approximate posterior functions. Therefore, we have an end-to-end differentiable model. Following depiction shows amortized SGVB re-parameterization in a VAE.

side note 2:

Note that in the above derivation of the ELBO, the first term is the entropy of the variational posterior and second term is log of joint distribution. However we usually write joint distribution as to rewrite the ELBO as . This derivation is much closer to the typical machine learning literature in deep networks. The first term is log likelihood (i.e. reconstruction cost) while the second term is KL divergence between the prior and the posterior (i.e a regularization term that won’t allow posterior to deviate much from the prior). Also note that if we only use the first term as our cost function, the learning with correspond to maximum likelihood learning that does not include regularization and might overfit.

Side note 3: problems that we might encounter while working with VAE;

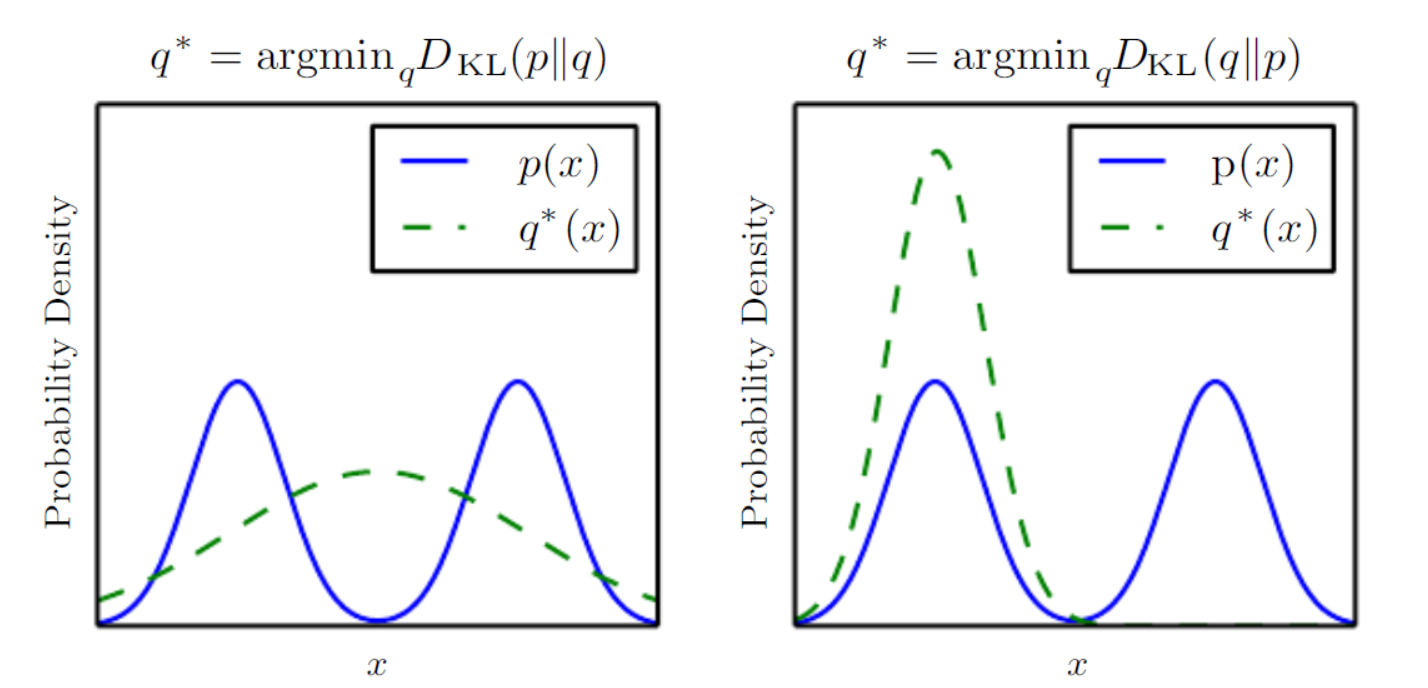

It’s useful to think about the distance measure we talked about. KL-divergence measures a sort of distance between two distributions but it’s not a true distance since it’s not symmetric . So which distance direction we choose to minimize has consequences. For example, in minimizing , we select a that has high probability where has high probability so when has multiple modes, chooses to blur the modes together, in order to put high probability mass on all of them.

On the other hand, in minimizing , we select a that has low probability where has low probability. When has multiple modes that are sufficiently widely separated, the KL divergence is minimized by choosing a single mode (mode collapsing), in order to avoid putting probability mass in the low-probability areas between modes of . In VAEs we actually minimize so mode collapsing is a common problem. Additionally, due to the complexity of true distributions we also see blurring problem. These two cases are illustrated in the following figure from the deep learning book.

references:

[1] Kingma, Diederik P., and Max Welling. “Auto-encoding variational Bayes.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6114 (2013).

[2] Rezende, Danilo Jimenez, Shakir Mohamed, and Daan Wierstra. “Stochastic backpropagation and approximate inference in deep generative models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1401.4082 (2014).

[3] https://www.cs.princeton.edu/courses/archive/fall11/cos597C/lectures/variational-inference-i.pdf